A loud rustling overhead has us craning our necks, frantically scanning the dense canopy for the source. There’s a brief flash of a dark limb and then whatever it is crashes away into the multi-hued greenery above us. Adi, our softly-spoken guide whispers a few words. Gibbon is the conclusion he gives with a half-smile, before he dips his head in a nod towards the departing primate and then strides off confidently along the barely visible trail.

The rest of us reluctantly follow, still checking the trees for any last glimpse of the primate. We’re excited and alert, our appetites whetted by the revelations of the camera trap we have recently checked. Through slightly grainy images we know that elephants, porcupines, sun bears, muntjacs, tapir, golden cats and even leopards have taken this same route, some within a few hours of our arrival. It's an incredible thrill to know that there might just be a leopard watching our progress from a concealed vantage point.

Yet it’s not leopards but actually tigers that have drawn us to this patch of jungle in central Malaysia. I am on a MYCAT tiger walk in the Sungai Yu Ecological Corridor, a protected strip of primary and secondary forest that flanks Highway 8 in the very heart of the Malay peninsula. The corridor, a mix of hilly stateland forest, plantations and privately-owned land is the site of three viaducts - raised stretches of the highway - built to offer a vital link for animals, and in particular tigers, to safely cross between the primary forests of Taman Negara national park in the east and the Titiwangsa Range in the west of the busy road. These are two of the largest forest areas in Malaysia and are home to some of the country's last remaining tiger populations.

A four-year survey that ended in 2020 estimated that there were just 150 Malayan Tigers, a sub-species of the world’s largest cat, left in the wild, though many believe that number might actually be even lower. It was estimated that the population stood at around 3000 in the 1950s. The The CAT Walks as they are officially called are part of efforts to safeguard them, a citizen conservation programme run by the Malaysian Conservation Alliance for Tigers, better known as MYCAT, an alliance of local and international NGOs.

One of the three viaducts that offer animals a safe space to cross underneath Highway 8 in the Sungai Yu Ecological Corridor

The MYCAT motto is ‘Saving Tigers Together’ and the walks are a crucial part of these efforts. Their aim is to raise awareness and understanding of the plight of these majestic animals that have been driven to near extinction due to poaching and habitat loss. Our walk has us on the lookout for evidence that tigers are using the corridor, as well as any evidence of any snares and traps set to catch them.

Fortunately, we see no evidence of the latter on our trek. And the good news, shared by Suzalinur Manja Bidin better known as Man for short, Deputy Director of MYCAT, who is leading this particular trek, is that evidence of poaching has dropped off significantly in the area since CAT Walk began. The gentle but clearly deeply passionate conservationist is on hand throughout the weekend to share more about the conservation group’s work and the challenges that MYCAT and the tigers they are trying to save still face. He also acts as our resident foodie, always able to find a spot where we can enjoy nasi lemak and wonderful homemade sambal at the mom and pop run roadside spots whose dusty verandas double up as makeshift restaurants.

Our specific trip is organised in conjunction with the Singapore Wildcat Action Group (SWAG) who have been supporting MYCAT, both in terms of raising awareness and funds since 2019. They run monthly trips where groups of six to eight participants enjoy a 3-day, 2-night experience. As well as the day-long jungle trek the weekend also includes a morning spent planting fig and pulai saplings, part of MYCAT’s efforts to rewild parts of the corridor that have previously been denuded by logging or illegal plantations.

Our base for the weekend is a small guesthouse in the settlement of Merapoh, in central Malaysia. It’s a quiet, but beautiful part of the country, a mix of small, sleepy hamlets nestled in the shadows of the region’s distinctive towering limestone karsts.

The imposing cliffs make the area popular with climbers and cavers, while Merapoh is a gateway to Taman Negara, one of the world’s oldest deciduous rainforests. Indeed, our guesthouse lies on the main road to the West gate of the National Park, which also doubles up as the route of our two night drives, an optional extra for the weekend trip.

These nocturnal excursions, undertaken in the back of a slow-moving pick up truck are certainly a highlight of the weekend. Our group of six nature-lovers, plus the driver’s wonderfully bored teenage daughter, brave the damp and chilly (for the tropics) night air to huddle together in the bed of the van as we use our torches to sweep the undergrowth in search of the tell-tale glint of eye shine. While a herd of cows proves to be a false alarm, we are also lucky enough to spot numerous palm civets gorging on the ripe date palms, as well as a number of leopard cats, a personal favourite. Not much bigger than domestic cats, their beautiful coats are a poetic mix of spots and stripes that prove ideal camouflage as they pick their way through the plantations on the hunt for rats and frogs.

Yet for me, the real draw of the weekend is the day-long walk in the forest, a mix of primary and secondary woodland, much of which remains untouched. Coming from the overly manicured parks of Singapore it is a simple joy to walk in woodland unimpeded by boardwalks, ropes and signs telling you where you can and can't go. Instead, we rely on old animal and logging trails that take us on a specially designed loop. MYCAT have developed a number of such trails on either side of the corridor, selected to pass through areas of potential risk from poachers. Our route takes us up and along an undulating ridge line via clumps of tall grasses alive with butterflies, dense bamboo thickets, sun-dappled forest clearings and concludes with us wading through a shallow but fast-running stretch of the Sungai Yu (Yu River) as we reluctantly head back to civilisation.

Throughout we are treated to the steady background hum of the forest, the buzz, creak, click and drone of the plentiful bees, crickets, and other bugs occasionally interspersed by the squawks, bleeps and trills of unseen birds or the distant whooping conversations of gibbons and siamang.

Of course, as anyone who has walked in the rainforest knows, it’s typical to hear much but see very little. The half-glimpsed gibbon, a startled bat, a passing changeable hawk and the disappearing rump of a smooth coated otter are all exciting but all-too-fleeting sightings. I also enjoyed a rather surprising encounter with a large Huntsman Spider that happened to be sitting on the underside of a leaf I had decided to pick up, while we all got to sample the inevitable connections with the forest’s voracious leech population.

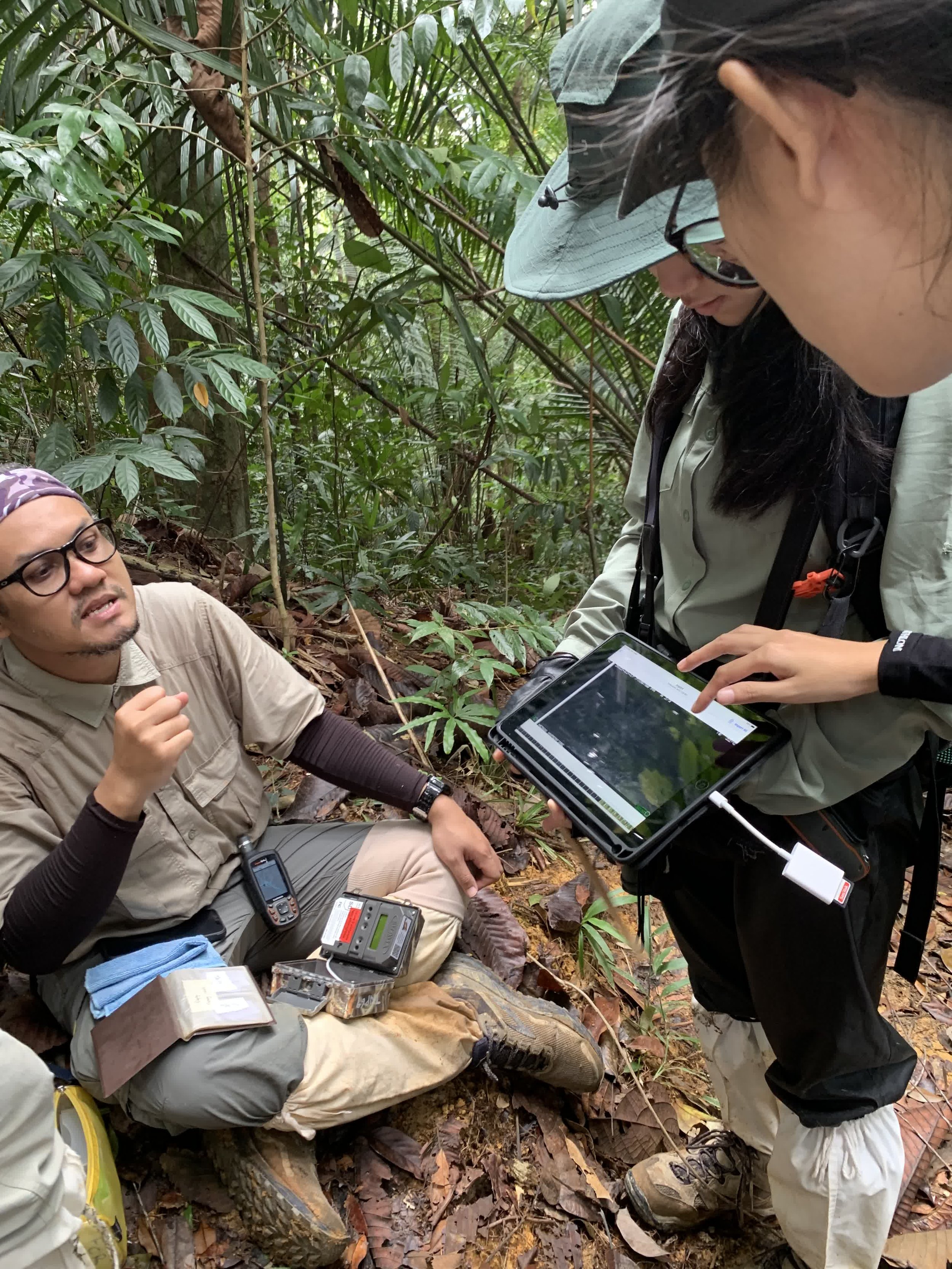

Our walk is also given an extra layer of richness thanks to having Adi (above left) and Man (above right) as our expert guides. Adi is a member of the local Batek, an indigenous community who traditionally enjoyed a nomadic lifestyle living off the forest for their needs. Now relocated to settlements on the edge of Taman Negara, Adi and many of his community still have incredibly close ties to the forest and retain a rich knowledge of how to read its many signs. MYCAT work closely with the Batek, employing some of the men as community rangers and women as seed gatherers for the tree nursery, tapping into their incredible expertise while also offering the community a source of income.

As he leads our group along barely discernible trails, Adi repeatedly demonstrates that forest craft as he pauses to point out almost imperceptible indicators that we are not alone. Claw marks left in a trunk by a sun bear looking for bugs, muddied bark where a forest elephant has stopped to scratch its belly and the barely visible prints of various animals help bring the jungle further alive.

Man, who has been working at MYCAT since 2007, also brings a distinctive level of expertise and insights, regaling us with his experiences of close encounters with tigers and other animals while out on patrol. What’s more he has some serious technology to support him, in the form of the multiple camera traps that dot our route. Each one is approached with a sense of genuine excitement and no little ceremony. From the unlocking of the padlock and chains securing the camera the tree, normally with at least one stifled squeak as some creature, be it wood ants, spiders or a lizard, grudgingly scurry from their nice dry hiding spot, to the slight pause as the iPad connects to the SD Card full of images, the sense of anticipation is palpable.

The biodiversity of this area revealed is incredible, with one camera trap capturing no less than ten different mammal species in the space of a few months. The exact locations and what’s been recorded on the cameras have to remain top secret to deter the potential for theft of the expensive cameras and poaching of the animals they record. Yet there are tangible signs that important wildlife are returning to the corridor.

MYCAT has around 30 of these camera traps placed around different trails across the corridor. As well as painting a more accurate picture of what is living in these woods they, along with the regular ranger patrols, help make sure that there are no uninvited humans visiting these protected areas.

That poaching is still a very real possibility is underlined when the sound of what could be voices floats over to us from the opposite ridge. It’s hard to tell exactly but it is enough to make Man pause, brow furrowed and take a few minutes to listen more intently. Again the noise floats over to us but it’s impossible to tell if it’s human or a bird. Adi thinks the latter, but just in case Man decides to report it after the walk and get a patrol to go check out the area.

Man stops to listen to a distant sound across the valley

It certainly serves to reinforce the seriousness of the conservation efforts that the walks underpin. The good news is that treks like ours, alongside the regular patrols are making a difference. During his introductory presentation around the large kitchen table at the guesthouse, Man, in between interruptions from one of the local cats, reveals that over 2000 people from 38 countries have taken part in helping to spot and remove over 326 snares and traps since the walks started back in 2010.

What’s more, our presence here also serves to have an impact on the local community as well. The tours are a very visible way to raise awareness of the ongoing conservation work in the area. What’s more, our trips to the restaurant down the road for breakfast pratas also show that there is a potential economic value that can come from protecting the local wildlife.

It’s something I would recommend to anybody who has any sort of interest in tiger conservation, but also anybody who would just like the opportunity to go hiking in a beautiful landscape with like-minded people. The chance to head into the forest was a joy in itself and something I am itching to experience again. Who knows I might even get to catch a glimpse of a tiger next time around.

Those in Singapore should visit SWAG for more details on upcoming walks and for other ways you can help raise funds to save the critically endangered Malayan Tiger. Those interested in hearing more about the status of the Malayan Tiger can watch this session from Singapore Tiger Week 2021, which features Dr. Kae Kawanishi, the manager of the Malaysian Conservation Alliance for Tigers (MYCAT) and Mr. Hazril Rafhan bin Abdul Halim, Senior Wildlife Officer of Malaysian Department of Wildlife and National Parks.

Looking smug after a morning planting